Ghost Farms and the Haunting of Main Street

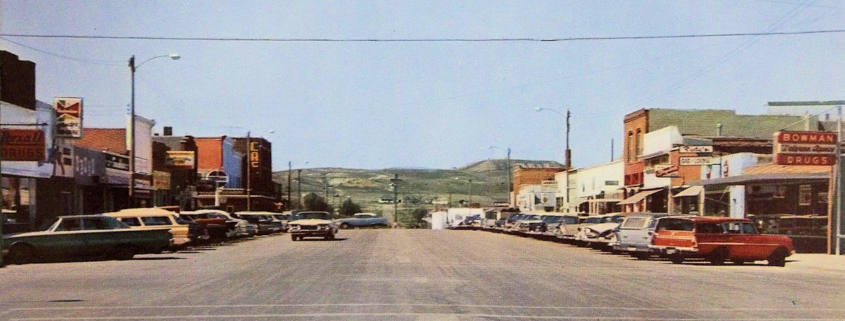

Like many North Dakotans my age, I have vivid memories of the thriving rural North Dakota downtowns of my childhood. Bustling stores with picture window displays lined Main Street. There were usually two law firms in each town so as to be able to represent both sides of disputes, several doctors and dentists, banks, grocery stores, and gas stations, one of which was always a Farmers Union Oil Cooperative. Each little town would have multiple churches: one was Lutheran, one was Catholic, and one maybe Methodist or Baptist. At the edge of town, multiple grain elevators towered near the railroad tracks, visible from miles away as farmers brought their harvests to town, brought their kids to school, purchased supplies, and sought fellowship.

In the early 1980s, those Main Street businesses, churches, and elevators were still buzzing. The “good years” for farming and ranching in the 50s, 60s, and 70s helped to keep a vibrant rural economy humming.

Like many North Dakotans my age, I have vivid memories of the thriving rural North Dakota downtowns of my childhood. Bustling stores with picture window displays lined Main Street. There were usually two law firms in each town so as to be able to represent both sides of disputes, several doctors and dentists, banks, grocery stores, and gas stations, one of which was always a Farmers Union Oil Cooperative. Each little town would have multiple churches: one was Lutheran, one was Catholic, and one maybe Methodist or Baptist. At the edge of town, multiple grain elevators towered near the railroad tracks, visible from miles away as farmers brought their harvests to town, brought their kids to school, purchased supplies, and sought fellowship.

In the early 1980s, those Main Street businesses, churches, and elevators were still buzzing. The “good years” for farming and ranching in the 50s, 60s, and 70s helped to keep a vibrant rural economy humming.

One vignette from the summer of 1982 illustrates the vibrancy of these small towns. Richard Woodley, the Life Magazine reporter from New York City, and I were driving back to Bismarck after a day spent with farmers. We stopped at a small town café to grab coffee and a sandwich. Like most businesses in the area with customer foot traffic, this café had an extra room — an anteroom — by the entrance with two doors. One door of the anteroom went to the outside street; and the other went to the inside of the business. The purpose of this extra room was mysterious to Richard, but he would have quickly figured out why it was there had he come back in the winter. This extra room is designed to capture the worst blasts of frigid winter air, and to give a person coming from the outside a space to stamp off the snow caked to one’s boots and shake off one’s hat, coat, and mittens. But it was late summer when Richard and I were there, and at that time of year the walls simply served as a community bulletin board.

When we finished, I led the way out of the café, opened the first and second doors, and went out to the car. To my surprise, the car was locked. Who the heck locked a car in North Dakota? And I seemed to have lost Richard, who had the keys. I walked back to the café, ready to tell Richard that there was never a need to lock a car in North Dakota because there was no crime, and besides, locking a car looked really wimpy. I found him standing in the café’s anteroom, staring at the wall. As I started to say, “Richard, you don’t need to lock ….,” he blurted out, “Look at this! This is amazing!”

He was staring at the wall with a bulletin board and some thumbtacked papers. It had facts about the community: population, year founded, names and home phone numbers of elected city officials, a list of schools, and city services. It had the meeting times for fraternal organizations for adults and clubs for kids, like FFA, Boy and Girl Scouts, and 4H. There was a list of churches with hours of their services and names of the preacher or priest. There was information on the parks, playgrounds, ball diamonds, and the swimming pool. A colored flyer announced the county fair, held in July when the farmers had a break from their labors. Thumbtacked papers announced more events, such as bake sales to support a community activity or project.

‘What is he so excited about? This is just a normal small town bulletin board,’ I thought to myself as I looked at it.

But Richard pointed to the bulletin board and said in an awed tone: “Look at everything happening in this community. My god! My high rise building in New York City has more people living in it than this entire town, but this community supports five churches, all these service clubs, ball diamonds, parks, and who knows what else!”

I’d lived in New York City too, during my years at NYU Law School, and one summer we were able to sublet a law school classmate’s fancy apartment on a high floor of a huge upper east side apartment building. As I rode up and down the elevator the summer of our sublet, no one would make eye contact with me. If I passed people in the hall or lobby, they would avert their eyes and alter their trajectory to avoid human contact. It was actually spooky.

Richard Woodley was right. More people lived in those big city high rises than in this little town. The contrast was vivid. In North Dakota, like many rural areas of America, towns were true communities. Never before had I realized that these ubiquitous bulletin boards were a sign of community vitality and energy. Back in 1982, bulletin boards and announcement walls just like this were in virtually every community café in North Dakota. They showed the health of those communities.

This memory of Richard pointing out the vibrancy of that small North Dakota town (unfortunately, I don’t remember which town) is now 40 years old, and most of the Main Streets of little towns like this one are much diminished and now struggling to survive. Why? Because the medium sized family farmers that once upon a time surrounded that community and others across our state are fewer and fewer in number, and those that remain face serious threats and challenges today.

I’ve spent years watching North Dakota governors announce their own economic development programs, crisscrossing the state with their economic development directors promising a new day for Main Street. These are usually well-intentioned programs, but for the most part they have been unsuccessful in stopping the decline of once-thriving small towns across North Dakota.

One of the overarching themes in recent state political campaigns by candidates from both major parties is how they will “revive” the rural economy by bringing jobs and opportunities to Main Street. They have slogans, programs, and platforms pursuant to which they promise this revival will occur. I wish them well but most of them seem off the mark to me. They won’t be effectual if they disregard family farmers and their critical importance to a thriving rural Main Street.

I believe that the relationship between the vitality and health of family farm agriculture and that of rural towns is inextricably linked. As the number of family farmers declines, the well-being of rural communities also declines.

This “mantra,” as I’ll call it to reflect my semi-religious fervor, is a personal opinion based on decades of observations and experiences working with and for farmers and rural North Dakotans as a lawyer, politician, and advocate. However, it is also rooted in rigorous research by highly qualified rural sociologists and academics.

Over decades, scores of studies have demonstrated that rural communities thrive when they are surrounded by mid-sized family farms. Studies also show that rural communities stagnate and suffer when they are surrounded by huge, industrial scale factory farms and concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

The famous Arvin/Dinuba study by Dr. Paul Taylor, an anthropologist working for USDA’s Bureau of Agricultural Economics, found that large scale industrial farm structures in one community were associated with adverse community conditions. On the other hand, smaller scale, owner-operated farms produced a thriving community with a higher standard of living. These findings have been repeated again and again in additional studies.¹

For those living in rural areas, it may seem that there are still many farms, but let’s take a closer look, by considering one state’s farmer population: North Dakota.

How many actual farmers do we have in North Dakota? Well, one source that should be accurate is the North Dakota Department of Commerce. In a fancy multicolored brochure designed to lure investment from out of state, it says we have 26,000 farmers, but the claim is highly suspect. Many thousands of “farmers” actually operate “farms” reliant on irrelevant but long-standing census definitions.

Here is a question to start discussion.

Is a person a farmer if he/she earns less than $2500 a year (gross not net) from agriculture? The US Census Department thinks so, bestowing them with official farmer status. In some instances, this is indeed true: there are incredibly innovative practices happening on the micro-farming level, tiny farms producing a highly specialized product for customers at farmers markets and restaurants. These creative agricultural endeavors shine with potential to scale up with added investment and training. However, I suspect the specialized micro-farm example is an exceptional case in our magic 26,000 farmer population figure.

I do not view myself as a farmer. However, I do own land in Mountrail County and for some years, my neighbor has routinely cut and baled hay from my land and then pays me by the bale.

He is a farmer and rancher. I am not. He has cattle. I don’t.

But the Census department counts us both as “farmers”. My neighbor, who is very courtly and polite, would nonetheless beg to disagree if I ever claimed to be a farmer or rancher.

I don’t blame the Census Department for this mess. It has been keeping census records since 1840 and for continuity, consistency, and validity of comparisons over the years, caution should prevail with any changes in definitions from one census to the next. The Census is scrupulous about providing precise definitions of its terms, and informing data users about its assumptions and procedures. However, I’m simply a landowner, which is quite different than being an actual farmer, raising crops or livestock.

When the Commerce Department says there are 26,000 farmers in North Dakota, they do not define their meaning of “farmer,” nor do they disclose this information about “ghost” farmers within the 2017 agricultural Census:

- 7,928 of these 26,000 “farmers” sold less than $2,500 in agriculture products per year;

- 888 of these 26,000 “farmers” sold $2,500-$4,999 in agriculture products per year; and

- 1,091 of these 26,000 “farmers” sold $5,000-$9,999 in agriculture products per year.

This leaves 16,093 farmers who grossed more than $10,000 per year from the sales of farm products, a low economic bar still well under a living wage.

Farm Types

Another way to try to ascertain a more accurate number of farmers is to check out the 2017 Census of Agriculture’s newer categories of “Farm Types” that supplement the older definitions.

- 3,425 “small family farms” with gross cash farm income (GCFI) of less than $350,000

- 4,441 mid-sized family farms, defined as a farm with gross cash farm income between $350,000-$999,999,

- 2523, large-scale family farms” with gross cash farm income in excess of a million dollars, and

- 1,106 “non-family farms” (without further explanation).

These economic-sized farm figures total 11,495. This leaves out 14,505 of our 26,000 “farmers” who don’t fit into any of these categories.

In 1982, it was very different. When Richard Woodley looked at that café bulletin, of the 36,431 farmers counted by the Census, 30,492 listed their principal occupation as farming and two-thirds of them (19,126) didn’t work off the farm for supplemental income.

In 2017, the Census changed its way of counting by considering multiple (up to four) producers per farm, but even with the extra people counted per farm only 20,184 of these producers considered their primary occupation as farming.

In summary, North Dakota has an agricultural crisis that has been building for many years. We have too few middle-sized farmers to sustain local communities, and the farmers who are still in business are in crisis: they can work hard, investing vast amounts of capital and labor, and still might not be able to support their families or pay their bills as large agribusiness continues to squeeze the producer.

What can be done?

First, all branches of government (state, federal, county, city) must recognize the impacts of the loss of mid-sized family farmers. We need government leaders to straighten the whiffletree of farm policy to provide more and better support to small and mid-sized family farmers.

North Dakota is economically blessed, with a portion of oil tax revenue set aside in the state’s Legacy Fund. As conversations intensify on how to spend the Legacy Fund’s billions of dollars, let us first remember the family farmers and the farm economy that made this state what it is today. “Plowing” money back into family farm agriculture makes perfect sense as it helps Main Street as well as the people living along the Rural Routes.

We can establish local processing plants, and implement new uses for agriculture products.

We can make the transition to a new generation of farmers possible by offering young and beginning farmers credit at the cost of money through the Bank of North Dakota.

We can create locally owned (not foreign-owned) corn processing plants.

We can support farmers fighting unconscionable behavior by farm suppliers and buyers through litigation.

We can provide generous scholarships and training programs for entry level farmers.

These suggestions are just a starting point. My main takeaway from this troubling intersection of declining smaller towns and the problems facing our family farmers is this: if an aspiring politician comes to you as a candidate for public office, and asks for your support, you should say, “Sure thing; I’d love to visit with you, but first: what are you doing for family farmers?”

To learn more about these issues and tangible ways you can help family farmers, wherever you live, visit the Learn More section of my website.

Studies:

¹ Dr. Curt Stofferahn, “Industrialized Farming and Its Relationship to Community Well-Being”, The Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems, 2014.