Meet Dwight Coleman, One of the North Dakota Nine

In the spring and summer of 1982, the national media began to hear of the farm crisis. Reporters and producers on the coasts went on a hunt for stories that illustrated the farmers’ plight. I was getting calls almost daily from the Washington Post, the New York Times, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and many others.

When they said, “I want to do a story about a foreclosure sale! Do you have any coming up?,” I was furious.

“I’m a lawyer fighting foreclosures!” I’d snap back. “I haven’t lost one yet, and I don’t intend to lose any. I’m doing everything that I can to stop foreclosures and forced sales against my clients. But if you want to watch a foreclosure, just come to North Dakota, pick up a copy of the Fargo Forum’s Friday agriculture supplement, and you’ll find pages and pages of auction sales and some foreclosure sales. Don’t call me again!”

A different kind of call came in the summer of 1982 from a reporter from Life magazine.

“Hi, I’m Richard Woodley, and I’d like to see what it is like for a farmer who is suffering from financial stress.”

I agreed to introduce Woodley to any of my clients who were open to talking to him. Soon, Richard and a photographer, Grey Villet (famous today for his photographs of the Loving couple in Virginia), showed up and set up camp in a Bismarck motel with a rental car, and an apparently unlimited budget.

Day after day, they came to my windowless basement office and I gave them directions on how to get to the farms and ranches of clients whose farms and ranches were within a half day’s drive of Bismarck—after getting an “OK” from the farmers. Richard and Grey went out, came back, visited with me, and even accompanied me on a trip to see a client (which was a bonus for me—they had an expense account to pay for the gas!).

Richard told me that they had visited with his editor and had presented an alternate story idea: instead of having the story be about the farmers, it would be a story about my work, as the farmer’s lawyer. “Would that be OK with you?”

“Yes,” I said. “If you and Grey will drive.”

That summer, they followed me to a picnic in Wolford, 170 miles north of Bismarck. I brought a stack of questionnaires with me. My class action was only in handwritten form, but I could “see” its eventual outlines in the same way that Grey could “see” the photographs he would eventually take and Richard could “see” the story he would eventually write for Life magazine. I had a stack of questionnaires for the farmers to fill out when we got to the farm. I was on the search for lead plaintiffs.

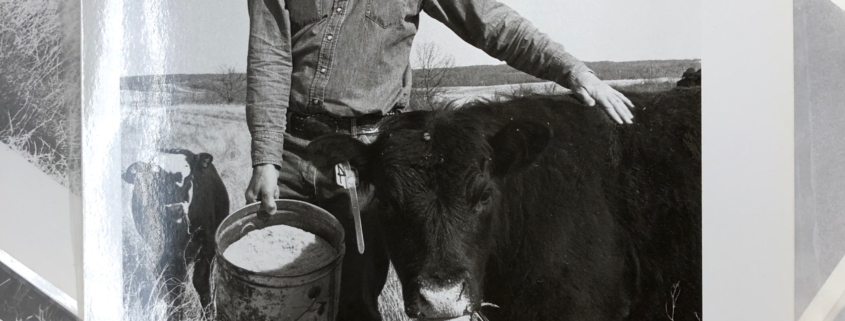

There were about fifteen farmers at the picnic that day and one of them was Dwight Coleman, who farmed in the Turtle Mountains, near the Canadian border. Dwight was a beginning farmer—he’d borrowed from the Farmers Home Administration in 1979, but by 1981 he’d fallen behind on his loan payments due to a series of catastrophic events, and instead of standing by him (as the agency had done with farmers during the Great Depression), they were threatening foreclosure if Dwight didn’t pay his full loan balance by Christmas Eve.

It was one of the cruelest stories I’d heard about FmHA’s tactics.

“I was under the impression that this beginning farmer program was supposed to be for more than two years,” Dwight said. He tried to fight back. “I said this is not right: you’ve got your appeals board and they’re the same people who were on the foreclosure board. What kind of a goddamn kangaroo court is that?”

Dwight first heard of me at another farmer’s auction sale.

“I didn’t know it was happening to everybody,” Dwight said. “I thought it was just myself.”

photo by Greg Booth

That day at the picnic, I told Dwight that a class action was a way to have a few “lead plaintiffs” represent and protect many other people who were in a similar situation (the class). I told him I needed to find class representatives to represent the 8400 farmers who were borrowers from FmHA.

Dwight was in. Here’s how he put it in his own words, when I interviewed him in 2019.

And because I listed the lead plaintiffs alphabetically in the complaint, Dwight Coleman’s name will forever be associated with Coleman v. Block.

(Secretary Block, by the way, was called “Auction Block” back in those days.)