The Greatest Peril, Part II

During 2016 and 2017, I would occasionally attend out-of-state meetings. At some of the smaller meetings, participants were expected to introduce themselves. I’d sometimes choke back tears and try to keep from weeping, “I’m Sarah Vogel from North Dakota, and I’m so sorry!” Why? I was ashamed of the way Morton County and the state of North Dakota had behaved during the historic gathering of indigenous people that became known worldwide as the Standing Rock DAPL movement.

Why was this so emotional for me? I’m all for spirited public debates (I’ve run for office myself and have worked for many political candidates and causes). But DAPL was different: in DAPL, the machinery of criminal law and military power were used to suppress debate.

I believe that whenever a government uses the machinery of criminal law or, even worse, military force, it is reprehensible. And it has happened before.

As I explain in The Farmer’s Lawyer, I grew up in the Nonpartisan League. The League’s leaders and members were repeatedly attacked by other political parties and in the press to suppress the NPL’s ideas on how to create an economic democracy and how to protect farmers and workers from the excesses of unfettered capitalism. I consider that kind of political fight a fair one: let both sides hash out their differences, hold rallies, criticize the other side, and so on. And the NPL tended to give as good as it got.

But between 1917 and 1920, key NPL leaders were attacked criminally for their opposition to the entrance of the US into World War I (although it wasn’t known then as World War I).

On March 13, 1918, the New York Times and papers throughout the country reported that A.C. Townley (pictured below), the President of the Nonpartisan League, and Joseph Gilbert, the membership director of the Nonpartisan League, were indicted in Minnesota for “issuing and circulating a seditious pamphlet tending to discourage enlistments.” They were both convicted by juries and sentenced to jail. Townley served his time and emerged an embittered man.

Joseph Gilbert (pictured below), however, kept fighting his conviction. He first appealed to the Minnesota Supreme Court, where he lost, and then appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

As a result of Gilbert’s appeal, a Supreme Court opinion was written that has influenced 100 years of First Amendment jurisprudence; an opinion that is even today deemed one of the greatest First Amendment decisions ever.

I can guess what you are thinking: Gilbert was acquitted. Hurray!

No. Gilbert lost at the trial court; Gilbert also lost at the Minnesota Supreme Court; he lost at the United States Supreme Court. Gilbert then spent a year in jail.

During the time he was jailed, petitions were circulated to get Gilbert a pardon, but he objected, saying he had done nothing for which to be pardoned. He later called his imprisonment “the height of nonsense.”

Gilbert emerged from prison as a hero to NPLers who knew he had been unjustly prosecuted.

He also emerged as a friend of the famous author, Sinclair Lewis, who used a true story about persecution of the NPL as a theme of his best-selling 1920 novel Main Street. Dig out your copy of Main Street, and read Chapter XXXVI.

But if Gilbert lost his appeals, why is the case Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U.S. 325 (1920) famous for its contributions to the First Amendment freedoms we enjoy (or ought to enjoy) today? It is because of Justice Louis Brandeis’s solo dissent from the majority opinion.

That dissent is now deemed by many constitutional scholars as the foundation for today’s principles of freedom of speech, freedom of press, and the right to privacy. It is also recognized for its contribution to the extension of those principles to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment. (The Fourteenth Amendment says “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of any citizen of the United States.”) Many cases, books, and commentaries have been written about this dissent.

Having freedom of speech to speak out (positively and negatively) about politicians, politics and parties should matter to all of us. Not only Black and Indigenous or Muslim speakers, but also white middle class Protestants should be vigilant about freedom of speech.

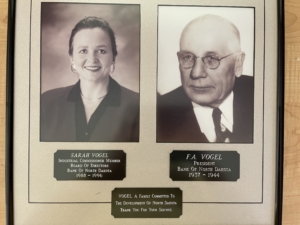

My sensitivity to protection of freedom of speech and assembly is grounded in part on knowing that an unjust criminal case was brought to suppress political speech in my own family. In 1934, my own (very respectable) grandfather Frank A. Vogel, who was then serving as North Dakota’s Highway Commissioner, was arrested and prosecuted for participating in a “conspiracy” to sell NPL newspapers. Yep. That happened. My grandfather was sentenced to 13 months in jail and fined $3000. Governor Langer was also fined, sentenced to a jail term, and removed from the office to which he had been elected by a landslide.

Fortunately, Langer and my grandfather were eventually acquitted. (See, Langer v. US, 76 F. 2d 817, at 826 [8th Cir. 1935]). My father, who watched the trial as a high school student, wrote a book about it: Unequal Contest: Bill Langer and His Political Enemies.

Governor Langer was reelected, and then elected to the US Senate, where he served until his death. My grandfather’s good reputation remained intact, and he later became manager of the state-owned Bank of North Dakota and was endorsed to run for Governor by the NPL.

Similarly, many of those arrested in the DAPL debacle have had their reputations burnished by being arrested. There are many, but I’ll mention only one.

Dave Archambault II, who was then Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, was arrested and charged with the crime of disorderly conduct when he protested illegal destruction of an area of significant historical and religious significance to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. At the trial, about a year after his arrest, the prosecutor said he “performed a political action and tried to get attention by getting arrested.” A jury acquitted him. Chairman Archambault later received many awards and was later invited to Geneva, Switzerland to speak to the United Nations Human Rights Council.

When any government official (state, federal, county, or city) threatens anyone’s freedom of speech and the right to peaceful assembly, the rights of all of us are threatened. We need to stay vigilant to protect the constitutional rights of everyone in order to secure our own rights.

Today, I see ominous signs that the oil industries’ suppression of protests through the enlistment of law enforcement is not over. The nightly TV news often includes brief mention that more arrests of Native Americans and their supporters have been made. Why? For standing and saying that a pipeline should not be allowed to cross wetlands and waterways. This time it is happening in Minnesota, at the Enbridge line.

But there is another path available to law enforcement: talking. In a neighboring county, same protests, but different results.