Why Farmers Make Such Great Clients

In the summer of 1999, Steve Jorgenson, a young farmer from northeast North Dakota called me about problems with his confection sunflower crop. In North Dakota, we call confection sunflowers “spits” because you spit the shell out, while eating the tasty inner seed.

Sunflower plants grown from good seeds have tall, sturdy, straight stems, with huge single flowers. But that year, Steve’s fields had multi-headed sunflower plants, with stunted, twisted stalks. Steve had spent a lot of money on the land, seed, fuel and machinery to grow his sunflowers, but this crop of deformed sunflowers would be worthless. He said he’d complained to Agway, Inc. (the breeder and seller of the seeds). Steve was still fuming over what the Agway representative told him: “It wasn’t the Agway seed that was bad; many farmers had used that seed and no one else had complained.” According to the rep, the poor crop was his own fault.

When Steve came my office a few days later, he brought another unhappy Norwegian farmer, Lorin Haagenson. They had been at a repair shop, chatting while waiting for parts, and discovered that Lorin had planted the same variety and his sunflowers were also deformed. What’s more, Lorin was also told he was the only farmer who had complained.

These two farmers reminded me of the problems I’d encountered on the east coast when I worked at the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs after graduating from NYU Law School. Since returning to North Dakota in the early 1980s, I’d often joked with my East Coast friends that farmers were just like the poor people being ripped off by shoddy furniture merchants in the Bronx. “Farmers are exploited in the same way. The only difference is that you have to add three or four or five zeros to the dollars at stake for farmers.”

I told Steve and Lorin that North Dakota had a consumer protection law, and we could also use breach of warranty theories. While I did more research, the farmer grapevine went into overdrive and within a short time I had the names of 90 farmers whose sunflower crops were just like Steve’s and Lorin’s crops.

We soon figured out how we’d proceed. I asked them to pick some farmers who would be in charge of raising money, reviewing my bills, communicating with the other farmers, and filtering questions. They loved the idea of splitting my hourly fee, which worked out to about $1.67 per hour per farmer. They promptly divided themselves into nine units of 10 farmers and each unit elected a “captain.” Then the captains met and divvied themselves into three regions, and elected a “team leader” for each region, with 30 farmers per region. These three team leaders (one of whom was Steve) would be in charge of raising money, communicating with the captains, and and setting policy for the case with me. It was slick. I had 90 clients, but I only had to deal with three farmers who had the trust of the other 87 farmers.

When the word got out that we were planning a lawsuit, Agway told the press that if we went to the North Dakota Seed Arbitration Board (a state entity with five top academic and government agriculture officials) and if they ruled in our favor, Agway would willingly pay the farmers. Agway didn’t have much credibility with me or the 90 farmers but we decided to give it a try. We put a lot of work into our petition for the arbitration and Agway responded, as expected, by denying all liability. Eventually, a one-day hearing was scheduled.

I met with the team leaders on how to handle the hearing and we decided to have several farmers testify in person and show a video collage of photographs and videos collected from many farmers.

The team leaders and the “star” witnesses came to Bismarck the day before the arbitration for final preparations. They brought boxes of photos, film, and documents for a professional videographer they’d hired.

But at the last minute, the videographer got sick and couldn’t make the video. My heart sank. How would we be able to present all the information?

A couple hours later, six farmers showed up at my office carrying boxes and bags. They had gone shopping for equipment to make the video themselves. I showed them to the conference room.

These farmers weren’t “techies”; they’d never made a video before! But it was obvious that they were delighted at the chance to face a very difficult challenge and figure out a solution. This is what farmers do every day, year in, year out as they deal with unpredictable weather, markets, and economic conditions. They are resilient and capable from long practice.

The next day in a packed hearing room on the ground floor of the capitol building, the very attentive members of the Seed Arbitration Board watched that video. It showed close-ups of deformed sunflower heads and scenes of entire fields of twisted plants with bizarre flowers. It showed farmers from various parts of North Dakota pointing out the same twisted stalks and deformed heads. The testimony and the images had a powerful effect.

The Board unanimously ruled in our favor, and said the farmers were entitled to substantial damages and Agway should pay. I think the video was the key reason for our win.

But Agway’s spokesman had lied when he said Agway would honor the results and findings of the Seed Arbitration Board. We had to go to federal court.

Agway’s management and legal team were used to mowing over farmers. Their lawyers tried to wear us out by scheduling all day depositions for all 90 farmers. They also tried to keep us from getting the benefits of the consumer protection law, claiming, “Those farmers aren’t consumers! They are businessmen and businesswomen.”

Although we were in federal court, the question of whether farmers were consumers was sent to the North Dakota Supreme Court, which ruled that farmers were indeed “consumers” of the seed and they could use all of the powers of the consumer protection law. This meant that the farmers would be able to get treble damages and recover attorney’s fees from Agway. The Jorgenson v. Agway decision is here.

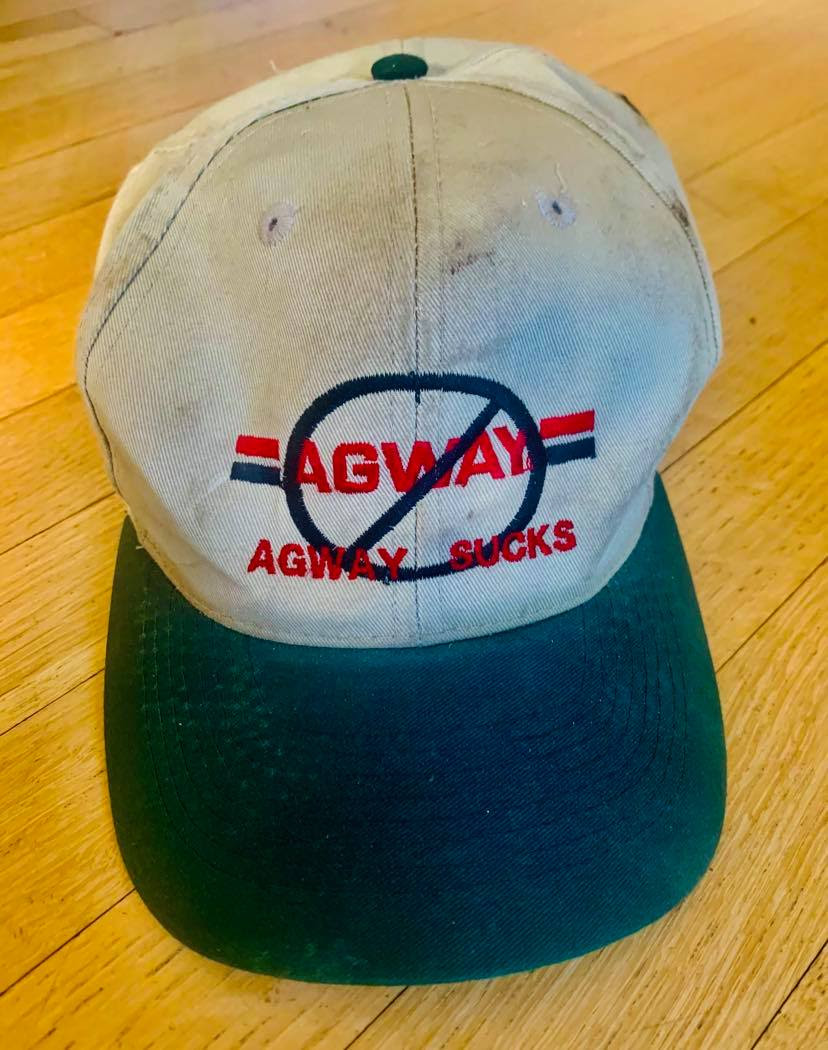

Agway’s legal team doubled down and kept on fighting, but the 90 farmers kept fighting too. They even made their own version of the Agway cap.

Paying $1.67 for an hour of my time wasn’t very much of a challenge to these farmers! Had they proceeded alone, the case would have been impossible. I enlisted Allan Kanner’s Louisiana law firm to help us. I’d worked with Allan on the Coleman v. Block case (the class action case featured in The Farmer’s Lawyer). Allan had become one of the top trial lawyers in America and he sent his colleague Conlee Whitely to join me at a deposition in North Dakota. During the deposition, Conlee mentioned that she flew in on the Kanner law firm’s private jet. And, glory be, at last Agway wanted to settle the case.

Agway insisted that the amount of the settlement be confidential. But Agway forgot to say we couldn’t celebrate.

The farmers found a big dance hall near Devils Lake with a big stage in the front, a dance floor in the middle, and a long bar at the back. They hired an old timey oompah polka band for dancing (it could have been this one with a 4 minute fun video — you can skip the ad at the beginning of the video). The plaintiffs brought their families and friends. Conlee even flew up from Louisiana to join us. Everyone knew that if the farmers had the money to hire an oompah band, the lawsuit had been successful—very successful.

Working on Jorgenson v. Agway, I learned that if one farmer has a problem, then it is likely that many other farmers will have the same problem. When farmers work together to seek a remedy, there are efficient ways for lawyers to create a big case that might even wrap up with an oompah band celebration.

The “Case of the Oompah Band” is one illustration of why I have found farmers to be such great clients.

Sunflowers image: “Golden Horizon” by North Dakota photographer, David Paukert

Photograph courtesy of

Photograph courtesy of